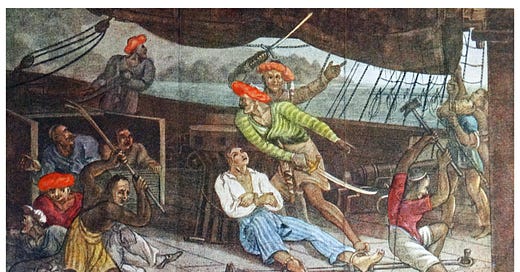

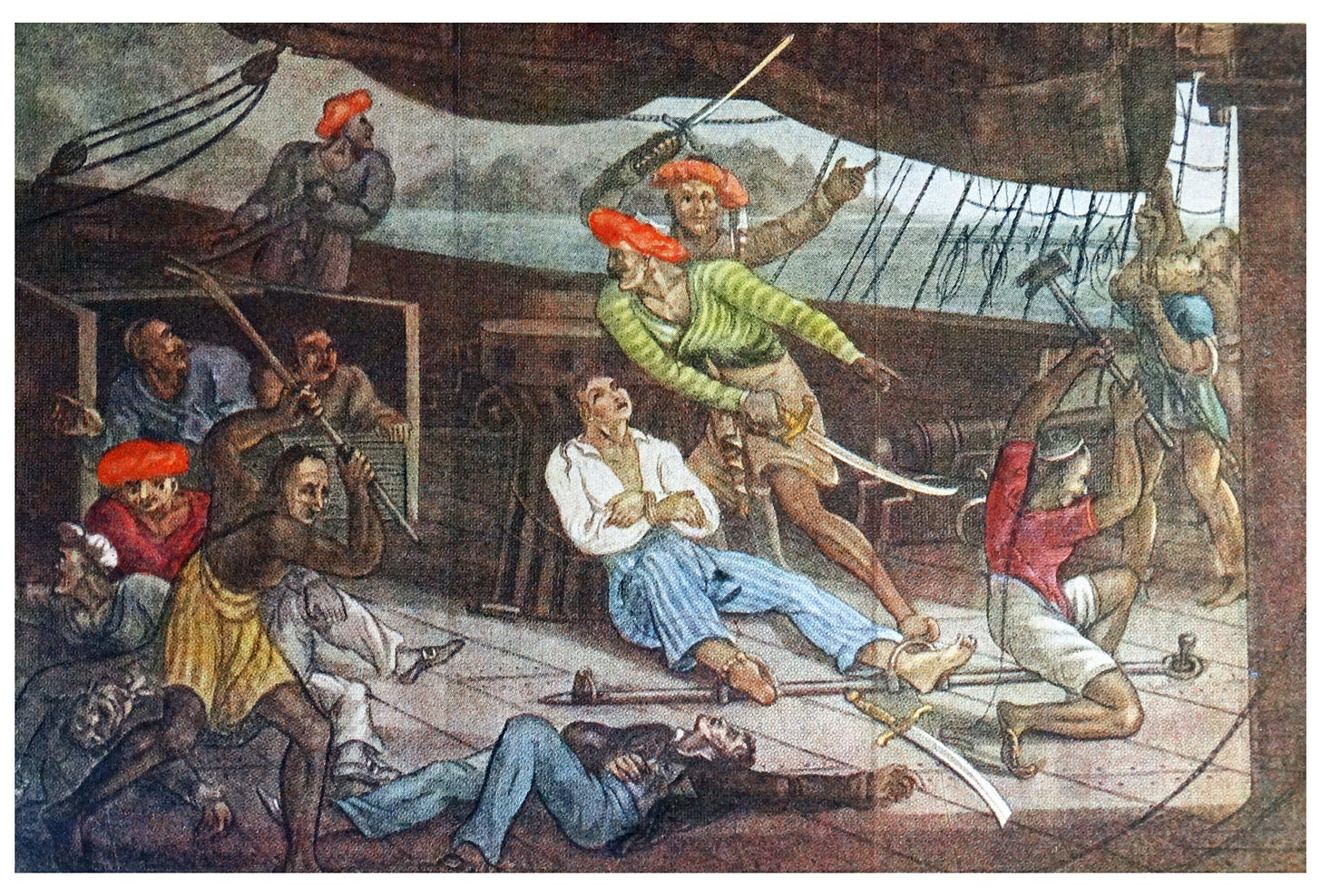

(Image: Mr Sharp, chief of the brig 'Admiral Trowbridge', is barbarously wounded, put in irons and spiked to the deck by pirates off Malacca 1806. 19th century Aquatint. Artist unknown)

The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) has reported an increase in the number of reported piracy and armed robbery incidents in the Singapore Straits. The IMB reported that in all 20 reported incidents during the first six months of 2023, the raiders boarded the vessels and weapons were reported in 8 incidents. The 20 pirate attacks or robberies so far this year compares to 16 in the same period in 2022, and none in all of 2019.

The increase in attacks in the Singapore Strait is in line with a global increase in piracy, by around 12% in the first half of 2023 compared with the same period last year. Of the 65 pirate attacks reported globally, 36 involved the crew members being held hostage. The IMB highlighted the incidents in the Gulf of Guinea waters as well as in the Singapore Straits. The IMB stated that the number of incidents increased, but not the severity as crews were usually unharmed.

The incidents of piracy and robbery in these seas are important because of the concentration of maritime traffic through the 1,000 kilometre Straits of Malacca and Singapore, which around half of all global seaborne trade and around one third of the world’s crude oil passes through. The straits are critical for Japan, with more than 80% of the country’s oil imports transported through the Straits according to the Nippon Foundation.

The long history of piracy in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore is worth bearing in mind. Piracy in the South China Sea, in the Straits of Malacca, and in the seas between the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia has been endemic for centuries. Piracy in the region has never been eradicated and has long historical roots on the coasts of Sumatra, the Indonesian and Malaysian coasts along the Strait of Malacca, the Philippines, and the south coast of China. Considering the complex coastal geography of the region, the territorial disputes amongst the littoral states, and the volume of vessel traffic passing through the South China Sea, piracy is not likely to be eradicated in the near future unless a major naval power projects force in the region with the acceptance of the littoral states.

There is a historical prevalence of piracy often resulting from the geography of archipelagoes divided by nation states and populated by poor coastal dwellers who make a living from the sea. This has been exacerbated in the past several decades as over fishing of waters in South East Asia by large international trawlers has led to declining catches for local fishing communities, leading to greater poverty, and fishermen turning to piracy for income.

Piracy in South East Asia has in the past several decades also been related to several Islamist terrorist groups in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia that use piracy as a means of raising funds or as part of their conflict with the authorities and jihad. This connection has been higher profile in the past several years as ISIS ideology has been associated with Islamist groups in Mindanao in the Philippines and have become the extension of the Caliphate claimed by ISIS in the region. Abu Sayyaf, an Islamist terrorist group with a history of engaging in piracy and other crimes such as kidnap for ransom, has been endorsed by ISIS leadership. A faction of the Abu Sayyaf Group led by Isnilon Hapilon pledged allegiance to the ISIS Caliph in June 2014 in a video posted on YouTube.

This is a region of fishing and seafaring people who have made their economic living, and in some communities their homes, on the seas. The national boundaries of the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia are not of primary importance to such people who cross the maritime boundaries of these states without concern for borders.

There are long established pirate centres on the south coast of Sumatra, on the Indonesian coasts along the Strait of Malacca. The continued pirate attacks during the 20th century during periods of major wars impacting the seas showed how ineffective the military, police, and customs authorities of states in the region were against piracy, and even how involved were corrupt officials from these countries. Corruption amongst law enforcement officials in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam is a key reason why piracy has not been eradicated in the region.

The Strait of Malacca has been the most consistent trouble spot for piracy attacks in proximity to Indonesia. Piracy in the Strait has existed for hundreds of years but the impact has become more severe with growing importance of the waterway for shipment of international trade. More than 300 ships pass daily through the Straits, which at their narrowest point are around 600 metres wide and 25 metres deep at its shallowest. This natural choke point is a risk concentration of vessels and geography that could be attractive for either pirates or terrorists.

The continued pirate attacks in the Straits illustrates the relative scale of the problem, but the failure to eradicate piracy in the region is due to geographical, economic, and political factors that have resulted in piracy being endemic in the region. Piracy has existed in the region for centuries but increased since the 1970s because of the huge increase in maritime cargo volumes, the growth of Asian economies in the 1980s, the poverty coastal dwellers and fishermen, and the availability of small arms for criminal groups since the end of the Cold War.

The reasons for the increase in piracy and robbery incidents in the Straits are likely due to the same reasons that have driven sea fares to crime for centuries: Changing socio-economic circumstances with many communities not recovered since the pandemic, as well as a lower fish catch due to climate change and the prevailing south-west monsoon. The economic situation leads some in coastal communities turning to robbery at sea to make any money. There is nothing new in the level of piracy in the Malacca and Singapore Straits, and it will certainly not change whilst there are coastal communities in Indonesia that suffer from poverty and do not see any benefits from global trade that passes in such huge volume past their homes.